A Wyoming mule deer herd is so riddled with CWD it could nearly vanish

(Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

FROM WYOFILE:

Preliminary findings have biologists worried for superinfected deer herd. There’s hope research could help guide chronic wasting disease management — if the public lets it happen.

WIND RIVER VALLEY—Biologists Tucker Russell and Rene Schell stopped in their tracks.

Spooked out of a daybed, a mule deer doe sprung to her feet. She bounded up a gentle, grassy slope amid badlands-like rock formations overlooking the Wind River, then froze, staring right back.

But Russell, with the University of Wyoming, and Schell, with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, had eyes on something else.

A still-spotted fawn.

Within moments, the youngster abandoned its hiding spot, bolting for mom. The doe’s days-old progeny complemented the high desert’s sagebrush steppe, which was in springtime bloom. Russell, a master’s degree student, snapped some photos of the fawn, a welcomed distraction from research that’s wrapped up in death. The Lander native is part of an effort to understand why this Wyoming mule deer herd is more infected with chronic wasting disease than any other.

After the fawn bolted, Russell got back to work, using a phone app to locate a GPS collar needing retrieval. A couple days before, it dropped off a still-living deer — one of the lucky ones.

Russell’s master’s degree work is part of a multi-agency study that’s exploring how migration and habitat use among animals in the Project Mule Deer Herd play a role in the transmission of chronic wasting disease, an always-fatal condition that’s on the rise in Wyoming.

The herd wasn’t chosen arbitrarily. It’s one of the most CWD-infected wild deer herds known to exist on the planet. Sky-high prevalence of the incurable prion sickness — three in four deer with antlers suffer from the disease in the core herd area — have long raised concerns for the well-being of the central Wyoming deer herd, which largely dwells within the borders of the Wind River Indian Reservation.

It’s still early in the study, which launched in early 2023 with 40 GPS-collared deer. Russell doesn’t even know which of the animals have or had CWD, although he will soon — even the living ones, thanks to a new testing technique that uses ear tissue.

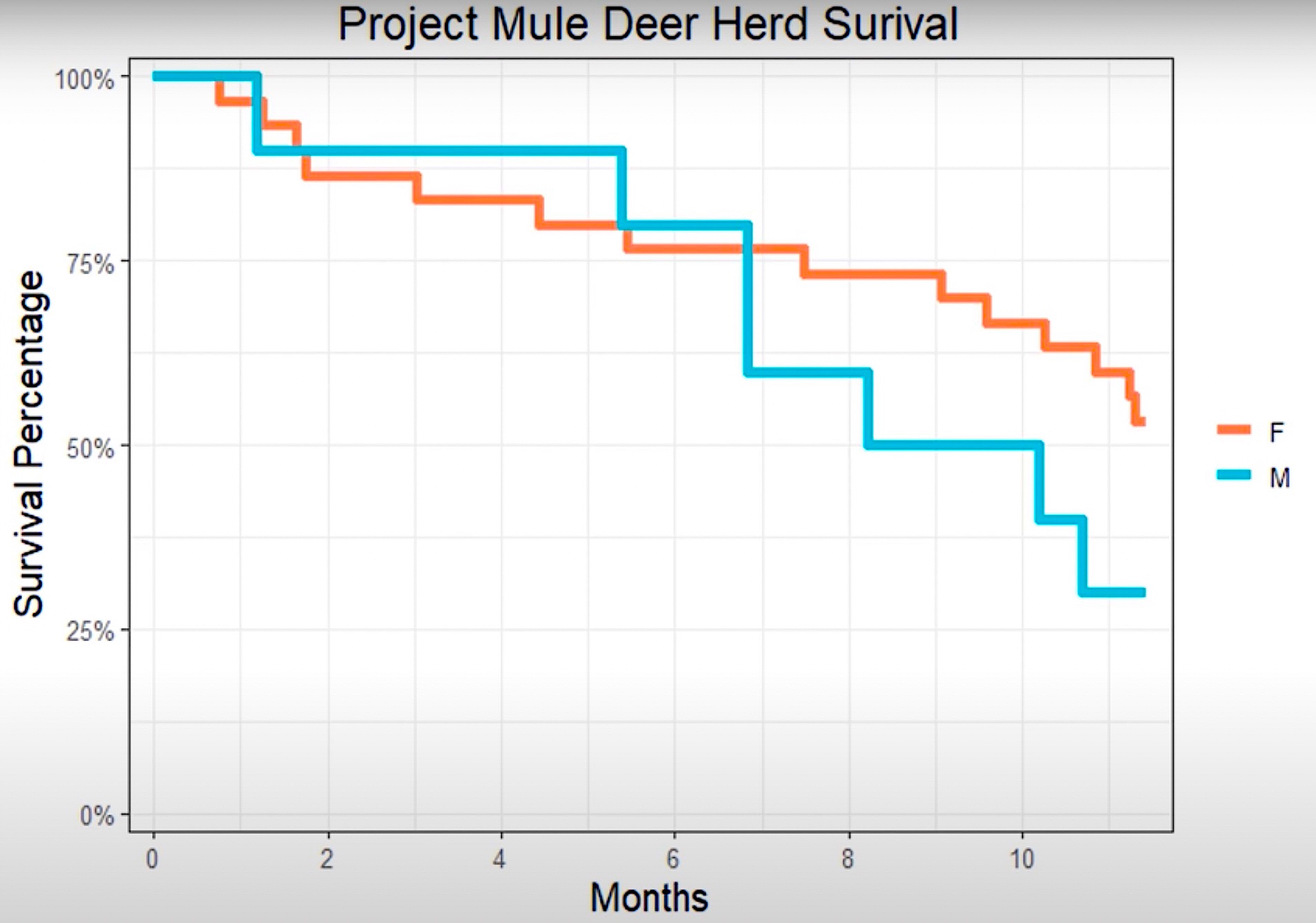

Ahead of the data dump illuminating how CWD-infected deer are using the landscape differently, an eye-opening discovery has emerged. The collared deer are dying at horrendous rates that threaten to wipe out the herd. Typically, adult doe mule deer have about an 85% chance of surviving any given year. In the Project Herd, however, only half of the first cohort of 30 GPS-collared does lived through their first 12 months as a research deer. The bucks, more prone to CWD, fared worse. Three out of the 10 tracked males were still breathing after one year, but by the time WyoFile rendezvoused with Russell some 15 months into the study, 90% were dead. A single buck remained.

Unlike in other portions of Wyoming, winter wasn’t to blame. Humans weren’t the direct cause, either. “We didn’t have a single hunter harvest,” Russell said.

‘Not going to have deer’

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department biologist whose district includes the Project Herd used the words “poor” and “awful” to describe the survival rates.

“We’re not going to have deer, at this rate,” Dubois-based biologist Zach Gregory said. “I don’t literally think there’ll be zero deer, but people should probably get used to not having many deer there.”

Coming up with survival rates and any demographic data on the Project Herd is meaningful because relatively little is known about it. Partly, it remains shrouded by the unknown because of the lines humans have drawn marking the herd unit and other boundaries. The core of the habitat is privately held property: agricultural land enabled by the Midvale Irrigation District, which is embroiled in a historic dispute with the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes over water rights. Project Herd mule deer that migrate into the herd area’s fringes in hunt area 171 tread into tribal lands outside of Game and Fish jurisdiction.

The state agency historically did not estimate the population because of those access hurdles, instead relying on hunter satisfaction and landowner surveys to gauge its status.

Satisfaction has steadily plunged: More than 80% of surveyed hunters were pleased with the experience as recently as 2018, but the last two years the metric is in the 40-50% range. Now, there’s a population estimate also.

In the winter of 2022-’23, the state agency conducted an inaugural aerial “sightability” survey of the Project Herd, Gregory said. The effort produced a first-ever population estimate of just shy of 6,000 animals. While there’s now finally a baseline, the biologist has a hunch that the count still needs significant fine-tuning. Many of the deer surveyed on tribal lands in hunt area 171, he said, were likely sojourners from the Dubois Mule Deer Herd.

Gregory is more confident in the estimate from the core of the herd unit around Pavilion, Ocean Lake and Boysen Reservoir. There, in hunt area 157, numbers registered at just shy of 1,300 mule deer.

Hunter-killed deer in this agriculturally dominated area have the highest rates of CWD. The region is among the first in Wyoming where testing is mandatory for both mule and whitetail deer.

The three most recent years of test results show that 74% of buck mule deer killed by hunters are in the process of dying anyway from CWD. Does — the reproducers that drive any herd’s trajectory — fare better, but still 41% test positive and would likely die within a couple years from a disease that turns cervid brains into swiss cheese. Even a third of the 1-year-old bucks have CWD. It means they won’t likely see the age of 3.

“When you start seeing the yearling mule deer have that high of a prevalence, that’s pretty alarming,” Gregory said. “Most herds in the state, you’re seeing animals that are older having [CWD]. Usually, younger animals like yearlings haven’t lived long enough to gather enough prions to make it a problem.”

Came on fast

Something about the landscape in northern Fremont County has allowed CWD to thrive. Prions — the misfolded protein vectors of the disease — can live outside of animal hosts, propagating through the environment.

“I think one of the things that’s very striking here is the speed at which this came on,” said Paul Cross, a U.S. Geological Survey research biologist who’s partnering on what he calls the Wind River Project. “Up until the mid-2000s they had almost no detections of CWD in this region. It was pretty low [prevalence], and then all of a sudden, over a 10- to 15-year timespan, it got to over 60%. That, to me, is pretty surprising for CWD — it’s pretty fast.”

Because there were no estimates of the Project Herd’s size while CWD ramped up through the 2010s, biologists and others are left to imprecise anecdotes to gauge its population effects. But by all accounts, the disease has walloped mule deer numbers, killing animals at a faster rate than they’re reproducing.

“Based on hunter observation, landowner observation and [Game and Fish] personnel observation,” Gregory said, “we’re not seeing the deer that we used to.”

Ken Metzler had a front-row seat to the crash. When WyoFile first discussed CWD’s impacts with the Riverton-area outfitter in late 2021, he estimated that his deer hunting operation had fallen off by 80%. Virtually every animal his paid hunters killed on leased agricultural hunting grounds — 98%, he estimated — tested positive for the disease.

Nearly three years later, Metzler reported that he’s given up on his commercial deer hunting operation altogether.

“We’re pretty well shut down,” he said. “I’m not booking any deer hunters. I can’t promise something that isn’t there.”

The 67-year-old outfitter has witnessed the Project Herd cycle in the past, and he retains some hope that it’ll bounce back.

“It’s getting worse right now, but it’ll turn around a little bit,” Metzler said. “If it comes back, it comes back — but it’s not looking too good right now, that’s for sure.”

Persistently high CWD prevalence rates don’t help the odds the herd will recover on its own. Even while deer numbers have tumbled, the lethal prion disease hasn’t let up, Game and Fish data shows. That suggests that animals are getting it directly from the environment — not each other.

Nevertheless, Gregory doesn’t want deer numbers to increase because of its potential to further exacerbate transmission.

“Hunter success is down and the number of animals harvested is down, but we’ve just got to maintain the same harvest, because we don’t want high deer density,” the biologist said. “We want to keep it low density, like it is. Maybe even lower.”

But Wyoming Game and Fish harvest reports suggest hunters have quickly lost interest in the area. As recently as 2020, Wyoming was issuing nearly 500 licenses in the Project Herd’s core hunt unit, 157. Nearly 60% of hunters actively used their tags, and they managed to kill an estimated 201 mule deer. The 2023 hunting season looked dramatically different: Only 126 licenses sold and fewer than 40% of hunters used their tags. Those who did killed an estimated 20 deer — 10% of the harvest from three hunting seasons prior.

Containing the contagion

Gregory’s aim for hunters to keep up the pressure on a collapsed population stems partly from a desire to contain the contagion as best he can, even if spread is inevitable. Through the CWD study, Russell, Gregory, Cross and other project partners have learned it consists of a mix of resident deer, short-distance migrants and animals that tread dozens of miles into the mountains and high desert — and they intermingle, also with adjacent deer herds.

“We’re starting to see more CWD headed upstream toward Dubois,” Gregory said. “We’re nervous that it’s an area they’re traveling back and forth.”

Dubois Herd mule deer, in turn, mix with Sublette Herd deer that summer in Grand Teton National Park and the Gros Ventre Range. It’s all linked by the marvel of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s migrations.

To try to limit the spread, Game and Fish increased the hunting quotas and extended the seasons in area 171, the Project Herd’s more peripheral hunt area.

“It was already pretty liberal,” Gregory said. “Again, we just don’t want a lot of deer in there.”

Data that Russell, the University of Wyoming graduate student, amasses on how CWD-positive deer are using the landscape could also help inform management decisions. Based on preliminary survival numbers, he expects that the herd’s long-distance migrants are the least likely to have CWD. Residents that never really leave agricultural land in the core hunt area, 157, likely have the highest rates, he said.

The coming CWD test results from the initial cohort of 40 research deer that have died in droves will help clarify the picture. An additional 42 GPS collars went out on another batch of mule deer in February, and scientists are expanding the research effort to include whitetail deer starting in 2025 to see how the species are intermingling.

“Whitetail deer CWD prevalence [in the Project Herd unit] is actually lower than the mule deer prevalence,” USGS’ Cross said. “That’s not typical.”

As the research matures, the window into the world of Project Herd deer should become increasingly clear. Eventually, Gregory might know exactly where animals are getting CWD.

“Through [Russell’s] work, we’re hoping to identify hotspots,” he said. “Then we could target [those areas] with some kind of license to remove deer — really reducing deer.”

Another possibility, the biologist said, would be to use fencing to keep the most contagious areas devoid of deer.

Wyoming wildlife managers could even turn to some of the methods they’ve been using to address overpopulated elk herds: Tactics like “auxiliary” hunts and paying technicians to kill elk, which stretch the boundaries of typical hunting-based big game management.

Whether the Game and Fish Commission will authorize outside-the-box changes to mule deer management to address CWD-superinfected herds remains to be seen.

Hank Edwards, a longtime Wildlife Health Laboratory supervisor who retired last year, said he and colleagues ran into resistance time and again when the agency attempted to manage the disease. It persisted right up until his last Game and Fish Commission meeting in July, when lawmakers and outfitters pushed back on plans to target more bucks as a means of addressing the lethal disease.

“When I left the department,” Edwards said, “the majority of [Game and Fish staff] just had given up on doing any CWD management because it had gotten so combative.”

There’s a contingent of management-averse Wyoming sportspeople, he said, who are “organized” and have been “able to shut down anything” biologists tried to do to address CWD.

“When you get to 65% prevalence, it ought to be bad enough that some of your detractors should at least let you try some things, but that hasn’t happened,” Edwards said. “How many people have to harvest a CWD-positive animal before the department is going to be allowed to do CWD management on any of the herds in this state?”

Recently, Josh Coursey, who heads the Muley Fanatics Foundation, caught up with a Fremont County rancher who pointed out that 75% of the alfalfa hay grown in the area where the superinfected Project Herd dwells gets shipped out of the region. Given that CWD prions can uptake into grasses, it made him wonder if the livestock feed exports were inadvertently spreading the disease.

“It was thought-provoking,” Coursey said of the rancher’s premise, “and it kind of gave me the shivers.”

Seeing the plight of the Project Herd, Coursey’s ready to see more aggressive CWD management.

“To do nothing is not the answer,” he said. “We need to be learning, and the only way you do that is by attempting things. We’re behind the eight ball.”

WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.

This story was posted on June 24, 2024.