Should the state provide life support to Wyoming’s ailing ambulance services?

FROM WYOFILE:

Most people expect an ambulance to arrive quickly when they call for help. But Wyoming’s EMS system isn’t funded like an essential service, and a critical failure can cost lives.

Bondurant sits about halfway between Pinedale and Jackson along scenic Highway 191 in western Wyoming. The area is buffeted by the Gros Ventre Wilderness, Hoback River, and both the Wind River and Wyoming ranges. From the road along the valley floor, you can see abrupt pine-tree-freckled hills and the snowy peaks of nearby mountains to the northwest.

The tranquil location is a draw to folks like Sam Sumrall and his wife, who retired there after moving from Mississippi. But it comes with risks.

“We lived in the country [in Mississippi], but we were literally five minutes from the hospital, five minutes from Walmart,” he said. “When we moved out here, we did so with the awareness of the fact that we weren’t going to have that luxury.”

Bondurant is part of Sublette County, the only county in Wyoming without a hospital. About 40 miles southeast on Highway 191, a new hospital under construction in Pinedale — the county’s largest community — is expected to open next year. However, the EMS crews based there are already covering 5,000 square miles with just a few ambulances.

In the winter of 2022-23, Sumrall was one of only three volunteer firefighters who lived in the town of around 100, all of whom only had basic first aid training and couldn’t transport patients. If someone needs to be transferred to a hospital, the closest emergency medical services are more than 30 minutes away. Life flights have to be used at times — but those can be expensive and take time to call in, too.

Response times are important because they can directly translate to the survivability of a medical event. That’s especially true for severe trauma, stroke and heart attack.

The scenery and limited taxes attract retirees to the area. But they should know about the limitations of EMS there, Sumrall told WyoFile in an interview last year.

“It’s not for everybody, it’s just not,” he said. “But, you know, we do everything we can to educate people.”

Since then, the volunteer group in Bondurant has grown to 10 people, according to Sublette County Unified Fire Chief Shad Cooper, thanks to support from those who were planning a luxury resort. However, that project is now planning to move elsewhere, putting future EMS sustainability at risk once again.

Bondurant’s isolation from emergency services isn’t unique. In fact, all Wyoming counties — and rural areas across the country — are considered EMS deserts.

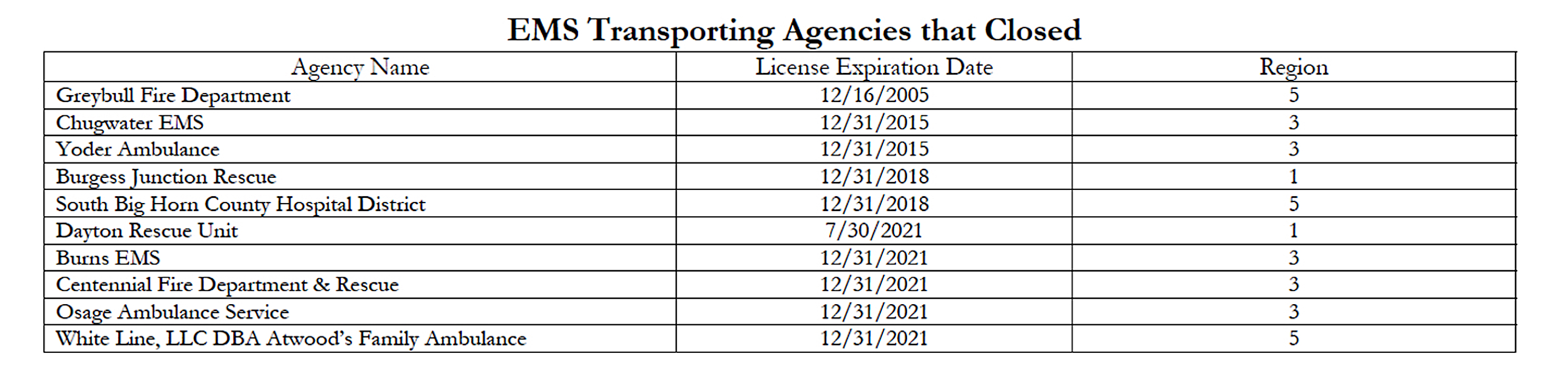

Providing emergency medical care has become increasingly challenging in a state with small communities scattered across wide open spaces. Across Wyoming, EMS agencies are grappling with funding struggles brought on by rising costs, declining volunteerism and insufficient levels of reimbursement.

Those challenges raise simple but profound questions. When we call 911, should we expect someone to arrive? Who should that be, and how long should it take?

And what are we willing to pay to save a life?

Expectations vs. reality

Andy Gienapp directed Wyoming’s Office of EMS for 11 years, and after leaving in 2021, is now deputy executive director of the National Association of State EMS Officials. He’s long known rural EMS was facing a money problem.

“I was trying to ring this alarm bell 10 years ago,” he said during a conversation last year.

Part of the problem is people take EMS for granted, Gienapp said. During presentations when he was working in Wyoming, he’d give local groups a scenario where the governor signed an order so counties were no longer required to provide certain expected services like snow removal and education. Locals were “aghast.” The order wasn’t real, he’d tell them, but the outrage was.

“And yet, we’re OK with not paying for what we all consider to be an essential service, and not paying for an ambulance?” he asked.

Gienapp noted that people still expect someone skilled to arrive in a timely manner if they call 911. That was backed up by the Wyoming Department of Health’s listening sessions in 2022, which found many people living in and around towns expected the best emergency medical care.

What people don’t often understand is the money that allows EMS to respond to medical emergencies is far from guaranteed.

EMS funding comes from a complicated patchwork of counties, towns, hospitals, property taxes, grants, insurance reimbursements and direct patient payments. EMS also operates under a variety of organizational structures ranging from private companies and hospitals to local governments.

That is to say, there’s not much funding uniformity among EMS agencies.

And an ambulance ride isn’t cheap. Those paying big bills for the service may wonder why EMS needs public money at all. But the problem is one Wyoming sees all too often: not enough people.

If no calls come in, or if a patient doesn’t need a ride to the hospital, EMS agencies don’t make money. If EMTs or paramedics are being paid by the hour, and the vehicles still need maintenance and expensive equipment, the math doesn’t work.

When the Legislature’s Labor Health and Social Services Interim Committee met in April 2023, health department officials noted that about 30% to 35% of 911 responses go fully unreimbursed because patients aren’t transported. Others are only partially reimbursed.

Meanwhile, to keep a Wyoming ambulance with basic life support running, it costs an average of $527,000 a year in staffing and equipment, the health department estimates. That translates to 650 reimbursed trips per year to just break even, which is hard to achieve for many Wyoming communities.

Advanced life support — utilizing more complicated procedures and medications to help those who need a higher level of care — costs even more.

“For advanced life support, 1,400 to 2,000 transports per year would be required to break even solely on a fee-for-service basis,” said Wyoming Department of Health Director Stefan Johansson, referencing the average.

Some point to the reimbursement-funding model as the original sin that made rural EMS so difficult to sustain. The concept for emergency medical services in the U.S. only started in the 1950s and became a robust, formalized system in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

To change it now would take every level of government, according to Dia Gainor, executive director of the National Association of State EMS Officials.

“That would require a very strong dose of federalism,” Gainor said. “And I’m using the textbook governmental term there, which means something collaborative at the federal and state and local level, because each one of those levels of government has a different capacity and different role to make change.”

Expectations have only increased since the ‘80s for vehicles that transport patients as well as training for the EMS employees. More time and training — and finding training opportunities that fit into a busy schedule — also translate into fewer people willing to volunteer their time.

Staffing

Nationally, EMS volunteerism is starting to slump, even though volunteers long made up more than 70% of the staff. A similar trend is true for Wyoming. Some blame complacency of residents, while others note the skyrocketing costs of housing, groceries and gas. Why not find a paying job to support your family instead?

Sumrall in Bondurant is in his early 70s, and said last fall that he wasn’t sure he could leave the volunteer fire department just yet.

“Personally, I want to make sure that the battalion is in good shape with a replacement for me before I leave, because the manpower shortage would just be magnified, especially during the winter months,” he said.

During an AARP webinar, Jen Davis — Gov. Mark Gordon’s health and human services policy advisor — noted that younger people are moving out of the state while older people are moving in.

“Some recent data that we saw in the last couple of months, Wyoming has one of the largest out migration[s] of our population, particularly in the younger generation,” she said in January. “Wyoming is up on in-migration. However, it is with older adults who are retiring and coming to Wyoming.”

She added that through the Wyoming Innovation Partnership, the governor’s office established a program to fund education and training for EMTs and paramedics. But, she added, “the program may run out of money quicker than we anticipated because of the need and the response so far.”

It can also be hard to entice career EMTs or paramedics into rural areas without enough pay, for which there’s no uniform amount. And once people get into the position of EMT, they tend to want to move up to paramedic, firefighter, nurse or doctor.

In Cody, EMTs received a pay increase a few years ago. Evan James Bartel, who’s worked there for three years, told WyoFile last summer he appreciated it. Things were tight.

“They did a tremendous bump last year, prior to which … I drove past every fast food restaurant in this town and saw they were advertising more starting [pay] than I was making here,” he said.

Bartel has since worked his way up to become a paramedic, a position that pays better and can perform more kinds of medical services. But the job is not about the money, he said. He loves helping the community and the diversity of challenges that come with the job.

Likewise, Braydon Bond was working to become a paramedic last August as one stepping stone on his way to medical school. EMS is great training for doctors, he said, but there’s not much financial incentive to work in it — it’s more about passion and training.

“I see EMS as the very fundamentals of emergency/patient care,” he said.

Staffing, funding for operations and inadequate wages are Wyoming EMS agencies’ greatest perceived challenges, according to the health department’s 2022 report.

At the same time, a major issue for reimbursement comes from those who either can’t afford to pay for their ambulance ride or who belong to government federal insurance programs. Reimbursement rates under the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services have barely budged compared to increasing costs, according to a 2022 report from national nonprofit FAIR Health Consumer.

About 40% – 50% of Wyoming EMS responses are for Medicare recipients, according to the state health department. That program is reserved for those over 65 and people with specific disabilities and conditions. It rarely reimburses for the full cost of a service, sticking extra charges with patients or, when patients can’t pay, the EMS agency.

Medicaid reimbursements are even lower than Medicare rates. States have some say in Medicaid — states like Idaho and Indiana recently increased rates for EMS — but it can be a hard sell for lawmakers who oppose new taxes.

Michael Petty is a volunteer firefighter with Sublette County Unified Fire living near Big Piney. His day job is working as a field safety specialist in oil and gas.

With decreasing funding from fossil fuels in Wyoming, Petty said, people won’t be able to count on the EMS services they’ve come to expect without paying for them in a new way.

“People still want to have really good care and be cared for where they live,” he said. “The money has to come from somewhere.”

Wyoming is one of 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid to cover more uninsured people here, leaving thousands who may not be able to pay ambulance and medical bills. The Wyoming Hospital Association has said that’s harming hospitals, many of which operate local EMS services.

Medicaid expansion could help, advocates say, but that would cost the state $22 million every two years, according to Department of Health estimates. The Legislature has discussed expanding Medicaid numerous times, but a fear that the federal government will someday leave states with the full cost has won out.

Essential service?

There have also been efforts to make EMS an “essential service” in Wyoming so every county or community must have access to it. More than a dozen states have done something similar, including nearby Colorado and Nebraska.

However, those efforts have failed so far here, mainly due to one key point: Many lawmakers don’t want to pass an unfunded mandate. The vast majority of counties — 21 out of 23 — maxed out the 12 levies allowed by the state last year. If communities are expected to fund EMS and can’t pass more levies, or if locals vote against a hospital or EMS district, where does money for the service come from? Funding for the schools? The roads?

For Luke Sypherd, president of the Wyoming EMS Association, if anything should be mandatory, it should be the crew of people responding to medical emergencies.

“There are other things that are certainly not essential to life or limb that are put ahead of emergency medical services,” he said.

County fairgrounds might be culturally important, but why should they get priority over a medic who can save someone’s life, he wonders.

To help sustain his own EMS agency within Cody Regional Health, Sypherd said he’s partially leaned on grants, amounting to about $3 million the last few years.

“Taxpayers here have paid taxes, and we’re trying to bring some of that back into our community,” he said.

But he hasn’t seen state lawmakers make the same effort to preserve emergency services.

“There’s this idea that’s circulated that we can’t afford it, and that’s completely false,” he said. “We choose not to afford it. At least the legislators of the state of Wyoming have chosen that they’re not going to afford stable EMS systems.”

At the statewide level, Sen. Fred Baldwin (R-Kemmerer) pushed for an essential service designation, noting that parts of the state — like the southwest — are struggling and now reaching crisis levels, he said. Baldwin is a physician assistant and volunteer fire chief in Kemmerer, but has worked with EMS in various capacities for decades.

“We’re losing services,” he said. “There are small places, small communities, where if one EMT is sick, and the other one is on vacation, and you dial 911, they don’t have an ambulance. There’s nobody there.”

Others are operating equipment that’s on its last legs, he said. Still, he acknowledged, funding is difficult when EMS is a money-losing business in much of Wyoming.

“Nobody wants to talk about raising taxes,” he said. “You know, you want things, but you don’t want to have to pay for them. It’s difficult. It’s a conundrum, and I don’t know the answer. I wish I did. I’ve been trying to find one for several years.”

However, Baldwin didn’t seek reelection.

Other lawmakers remain skeptical.

“Given that only 13 states have said that EMS is essential, I don’t see the need for Wyoming to do that,” said Jeanette Ward (R-Casper), voting against an essential service designation last April. “And I think that generally, in general, when people call for an ambulance, one shows up.”

Another solution: Community EMS

Johansson and the governor’s office has asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services — generally referred to as CMS — to rethink how the federal government reimburses EMS calls in rural areas, he said. While rates are hard to change on the federal level, he suggested Medicare could reimburse for “community” EMS.

“Meaning that there’s more of a community-based approach that doesn’t require a trip to the hospital to kind of satisfy payment conditions,” he said.

That is, he wants EMS agencies to be reimbursed for helping someone in their home instead of only getting money for a transport, something he’s mentioned Wyoming Medicaid has started to do.

It’s an idea that Sypherd with the EMS association has said so far hasn’t generated enough money on the ground, especially as major payers like Medicare won’t reimburse for it.

“Right now, you are not going to get enough money to support yourself out of community EMS,” he said.

When Johansson has asked CMS to start implementing this kind of community paramedicine reimbursement, he says agency officials will often just say they understand Wyoming’s challenges and “we’ll communicate that up the chain.” Then, nothing happens.

CMS did run a pilot program for something similar called ET3, or the Emergency Triage, Treat, and Transport model. That program reimbursed EMS for transporting patients to facilities like urgent cares or to primary care providers instead of hospital emergency rooms. It also reimbursed agencies for treating patients at home or via telehealth.

However, that experiment ended two years early on Dec. 31, citing “lower-than-expected” participation and administrative costs exceeding potential long-term savings. Of the program’s 152 participants, none were in Wyoming.

In the meantime, Johansson remains frustrated with CMS’ lack of follow-through, and said his office and the governor’s office will continue to push for new reimbursement models.

“It is frustrating that one of the — if not the — largest payers of this type of service has kind of been somewhat intractable on those policy changes,” he said.

But some individual EMS agencies, he added, are requesting enhanced CMS reimbursement rates, arguing they should be considered the sole critical access medical provider in a rural area that may also include a nearby fire department.

Some involved in EMS suggest U.S. Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.) could help spur CMS into action because of his medical background as an orthopedist. The senator didn’t return emails and calls for comment.

WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.

This story was posted on August 26, 2024.