Landslide exposes Jackson Hole’s frailties, community strengths

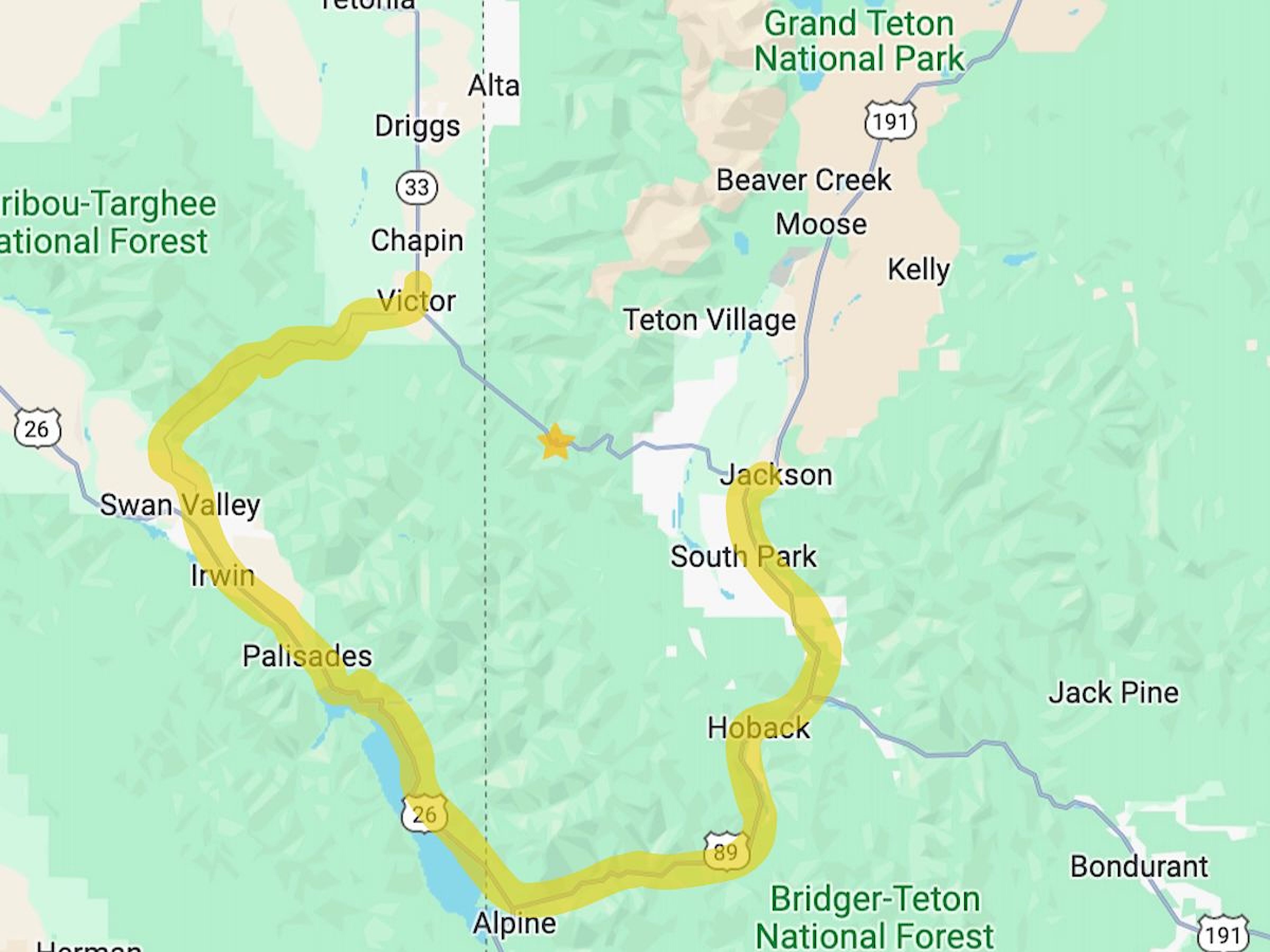

The detour from Victor, Idaho, to Jackson is highlighted. A star marks the site of the landslide on Wyoming Highway 22 over Teton Pass. (Tennessee Watson/Google maps)

FROM WYOFILE:

The closure of a single road highlights the vulnerability of the foundation that supports a mountain community’s robust tourism and lifestyle economy.

Each weekday morning, thousands of people in eastern Idaho get in their cars and trucks to commute over Teton Pass to work in Jackson Hole, one of the nation’s wealthiest communities. A typical trip takes about 40 minutes.

That was until June 7, when a landslide destroyed a section of highway that traverses the pass. Now, that same commute from Victor, Idaho, takes two hours or more each way. Traffic heading through the Snake River Canyon detour has started congesting at least 40 miles from commuters’ destination.

Adding four hours of driving to an eight-hour shift in a community where many working people were already struggling to get by is simply not sustainable for some commuters, who worry about children, pets, homes and gardens. That a single road closure could cause so many problems for those already living on the edge has spurred questions about the sacrifices workers make to keep the mountain town’s tourism and luxury real estate industry booming.

“It’s way too long,” said Selena Humphreys, operations director at the Teton Raptor Center in Jackson Hole, who lives and commutes from Victor. She missed a play day with her 7-year-old daughter, then two more family days as she bunked in once-nearby Jackson Hole town of Wilson to fulfill weekend shifts.

“I’ll be missing out,” she said of her family life. “They are there and I am in Wilson. That commute is just not realistic.”

One could estimate that some 7,500 or so commuters are traversing the Snake River Canyon detour route each morning and evening, based on state traffic counts, employment figures and other social data.

The congested Snake River Canyon highway detour route between Alpine and Jackson saw fewer than 1,800 vehicles on an average morning or evening three years ago.

“It’s just not sustainable,” said Crystal Wright, a Victor, Idaho, skier, fitness coach, gym owner and mother to a 6-year-old daughter. A 15-hour day last week left her too exhausted to talk that evening.

“I was complaining about the commute before the traffic went around,” she said after a night’s decompression. Now, “it’s dangerous.”

Beyond the spud curtain

The Jackson Hole community and local, state and federal agencies have responded vigorously to the crisis. A Facebook page offers ride shares, couches to surf, pet sitting and other free help. The county relaxed camping rules for commuters, commuters’ bus fees are paid for by a tourism lodging tax, and the Community Foundation of Jackson Hole is connecting them with Jackson Hole residents who have empty beds.

Gov. Mark Gordon declared Big Fill Slide, as the Wyoming Department of Transportation named it, to be an emergency June 8, allowing the state to request federal aid. U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg posted on X, the website formerly known as Twitter, the next day that his agency was reaching out to Wyoming highway officials to help.

Buttigieg traveled Monday to Cheyenne to be briefed on the Teton Pass calamity and showcase President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The disruption has raised questions about how the Jackson Hole area got in a predicament in which the failure of a single highway could unravel an otherwise prosperous and vibrant community. Jackson Hole’s location at the doorstep to Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks, some argue, has turned a once quaint and laid-back mountain town into a tourism/lifestyle/real estate destination without the infrastructure required to sustain the growth.

Real estate prices are beyond the reach of many local workers. Satellite communities have blossomed over Teton Pass in the Driggs-Victor area, and down the Snake River Canyon in Alpine and other Star Valley towns. Commuters drive from Sublette County, too, through the winding Hoback Canyon.

“We’ve been too big for our boots for 20-25 years,” said Jim Stanford, a former Jackson Town Council member. “‘More and more of everything’ seems to be the operating principle in Jackson Hole over the last 20 years.”

“The pass being shut down is the universe taking a highlighter to the issues in the town,” said Jenny Fitzgerald, executive director of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance. “Everybody, in some capacity, is feeling it.”

The highway failure shines “a very bright light” on the community’s economy and social structure, said Jonathan Schechter, a Jackson Town Council member and economic consultant. The wound reveals “almost a bottomless well of different public policy issues, questions, decisions.”

Growth in Teton County has been debated for decades, said Rick Howe, president and CEO of the Jackson Hole Chamber of Commerce. “Forty years ago people were talking about capacity numbers,” he said. What followed was “decades of probably not paying as much attention,” to the jobs-to-housing ratio as what was needed.

Yet, Howe said, “this doesn’t have to do with growth,” pointing to the area’s geography. “Slides happen [or] there’s too much snow.”

The crisis, “I’m not sure it’s a function of the size of the economy,” said Andy Schwartz, former state representative. He pointed to the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore as “almost an analogous situation.

“There’s never a guarantee of transportation networks,” Schwartz said. “They fail.”

More and more?

Even before three communities in two states were forced to grapple with a crisis that has been lurking all along, the town of Jackson ran headlong into what leaders saw as a step too far. The Utah company Mogul Hospitality Partners proposed a single, three-story building at the town’s north entry that the Jackson Hole News&Guide declared was “the size of four Target stores.”

The building would have 171 hotel rooms, retail stores, bars, restaurants, a fitness center and spa, 36 condos and a faux Moulton Barn, a recreation of the iconic pioneer structure in Grand Teton National Park. The plan was front-page news for weeks this spring as the Jackson Town Council enacted an emergency moratorium to stall the development until officials decide whether building regulations are out of whack with the town’s character and residents’ desires.

Valley residents also have rallied to prevent development on state school trust land in Teton County, offering to lease a 640-acre parcel for recreation instead of development. The Legislature had targeted state land in the county for development and increased revenue, an effort to ride on the coattails of the region’s success.

“We already have too much growth and development activity here,” said Judd Grossman, an outspoken valley musician. Part of the problem is tourism promotion, he said, which is fueled by a lodging tax on hotel rooms used mostly to draw visitors. Some of those tax dollars are earmarked to offset their impacts by supporting things like the START bus system.

But what was formerly a local tax that voters had to renew every four years to boost the county’s budget is now imposed statewide due to 2020 legislation. Wyoming collected $25.6 million from the tax in Teton County in 2023.

When tax renewal was an issue to be decided by town and county voters, it fueled vigorous election campaigns for and against its imposition. Now, local residents don’t have a say.

“The lodging tax is bad because you’re using public money to subsidize private business in Jackson Hole,” Grossman said. “Let’s let it sell itself passively,” he said of the valley, “and not add fuel to the fire.”

Some state lawmakers believe they could solve the community’s problems, perhaps by wresting other forms of local control from towns and counties through legislation that would be forged by a legislative Regulatory Reduction Task Force. Last year, the panel sought to strip local authority over accessory residential units, a move that could essentially double the density of many single-family neighborhoods producing more housing, but without any review of available essential services or the guarantee it would be affordable.

The task force will continue its work until the next legislative session early next year, with an eye toward easing development regulations. How the state’s effort, which favors the free market, jives with Teton County and Jackson’s own efforts to resolve the worker housing problem remains to be seen.

Failure of Teton Pass Highway 22, “I wouldn’t like it to be an excuse for more development in town,” Grossman said.

A stronger bridge

Failure of the Big Fill, the built-up Teton Pass roadbed that the landslide undermined, “reminds us that the Teton County/Jackson Hole economy depends on friends and neighbors commuting from Lincoln County [Alpine/Star Valley] and Teton County, Idaho,” said Len Carlman, an attorney, a former director of the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance and a candidate for the Teton County Board of Commissioners. “We need to invest in affordable housing in Jackson Hole for essential workers,” the Wilson resident said.

“Our community has seen the challenge and reached into our toolbox,” he said, ticking off $80 million in voter-approved taxes for community initiatives. The 1% sales tax generates about $22 million annually for voter-approved projects.

“St. John’s Health asked $24 million for workforce rental and overnight lodging and the community said yes,” Carlman said. The school district asked for $16 million for employee housing “and the community said yes.”

Elected officials sought $10 million for town of Jackson employee housing, another $10 million for county employee housing and $20 million more for community housing.

“And we said yes,” Carlman said. “It’s not enough, but it sure is more than nothing.”

Pundits see serendipity as a factor moving Teton County’s housing situation to the front burner. When a highway or bridge goes down unexpectedly, “We’ll build a stronger bridge,” Carlman said. “That’s what human societies have done forever.”

Workers who commute from outside Jackson Hole made some sort of trade-off, Jackson council member Schechter said as he shed his usual sympathies for a steely-eyed look.

“It’s a horribly cold, economic-analytical way of looking,” he said, but “the worker has made the decision that they are going to live in Idaho based on an infrastructure that gave them confidence they could get to work on time.

“They could live in a much smaller, crowded place,” in Jackson, he said. “Presumably they are making a choice.”

Jackson Hole can’t abandon its tourism lifeblood, the Chamber’s Howe said. Visitors in 2023 spent approximately $1.7 billion in Teton County alone, 36.8% of the state total, according to the Wyoming Office of Tourism. Tourism supported 8,200 jobs in the county last year, Howe said.

Industry leaders tout the county’s Sustainable Destination Management Plan as a method of ameliorating the effects of the crowds.

If the state and community stops promoting tourism, “then somebody tell me how we exist as a community when that’s what provides the fuel to the valley,” Howe said. “You still have to tell people who you are.”

There may be no way to change Jackson Hole’s identity. “We have to stay afloat as a town that’s based on tourism,” said Fitzgerald, the Conservation Alliance’s director.

Cracks reveal resilience

Meanwhile, commuters wend their weary ways back and forth as the Teton Pass highway is repaired temporarily, work that officials say could be done in a week or so.

Wright, the mountain-athlete mom, moved to Victor to have a suitable home with a place for horses. Engaged in a business routine reliant on a single road, “you get kind of complacent,” she said, “and forget about the big picture.”

She’s been in ads promoting Jackson Hole but also believes advertising “could be toned down a bit.

“Tourism is such a part of our community,” she said, but it’s “gotten a lot more out of control.”

“There should be more housing options,” Wright said. “There hasn’t been as much action taken as could be.”

Commuting-mom Humphreys may see an emblem of the situation — a lost opportunity to nourish her daughter’s growth — in her own backyard.

“We’ve basically abandoned all hopes of our vegetable garden this year,” she said.

While some of her plans and dreams wither on the vine, Jackson Hole continues to grow.

WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.

This story was posted on June 17, 2024.