Historical fiction author delivers a surprising ode to Johnson County War figure Nate Champion

By Susan Monaghan

Gillette News Record

Via Wyoming News Exchange

GILLETTE — What makes someone courageous? Is courage a mandated act — a necessary reaction to a set of circumstances not worth experiencing?

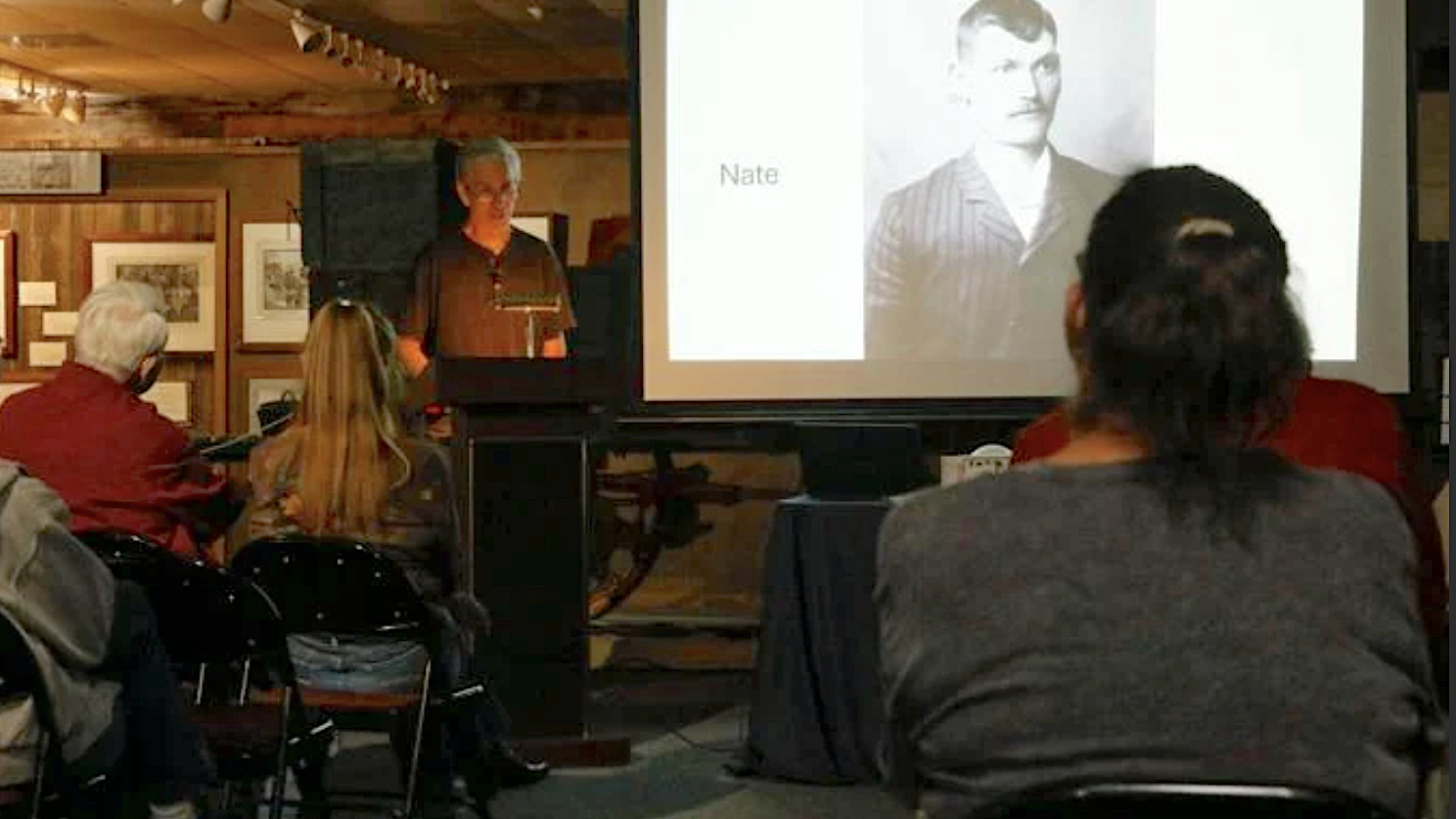

For historical fiction author Mark Warren, who visited the Campbell County Rockpile Museum to deliver a presentation on Johnson County War figure Nate Champion on Thursday, the alchemy of courage has been mandated study since he was a child.

“I grew up in a family dynamic that wasn’t healthy. I was afraid of my father,” Warren said. “(And) I was fascinated by courage … it was something I studied.”

The 76-year-old has been practicing courage for as long as he’s been studying it. Besides being an environmental educator for the Georgia Conservancy for over 10 years, he was also an avid whitewater racer — and longbow shooter — and won awards for each, according to the website of the conservancy school he founded, Medicine Bow.

Warren wasn’t hugely forthcoming about his resume after his presentation on Champion, a small-time rancher who challenged a powerful Wyoming cattle baron association and was murdered in the 1890s.

The priority was Champion.

In the back of a dimmed artifact display room, the hour-long presentation on Champion’s rise and fall cleanly documented his final standoff against a small army of gunmen in his cabin at the KC Ranch.

By the time Champion was killed, he had concluded “one of the greatest last stands in history,” Warren said. The audience was invited into the scene of a killing with the import of a much grander injustice: it was the power of an entrenched monopoly against the many excluded.

Against odds that cruel, how long would the average man hold out, alone in his cabin? In Warren’s telling, the siege lasted eight hours. That singularity is exactly what attracted Warren to start seriously studying Champion five years ago.

Warren said that for a man like Champion, it was enough for him to know he was in the right.

The Nate Champion story

Warren’s telling of the story of Champion is essentially a story about the Wyoming Stock Grower’s Association, a cattle organization founded in 1872 by wealthy European and east coast settlers that had an enormous influence on the politics of the Wyoming territory.

Champion was one of many small-time ranchers in Wyoming excluded by the WSGA.

As Warren tells it, Champion had several run-ins with WSGA members that earned him a reputation as an enemy of the club.

Several times, Champion was investigated by WSGA employees looking to find dirt on him. The employees weren’t able to prove he’d even so much as stolen a single calf, Warren said.

Gunman hired by the WSGA tried to kill Champion twice while he was settled near the Hole in the Wall pass in Johnson County’s Big Horn Mountains, according to Warren.

In their final attempt, WSGA member Frank Wolcott hired more than 20 gunmen to kill 70 suspected cattle thieves, a charge meant to defame competing small-scale ranchers and other enemies of the association, in Johnson County.

That would include Champion, who had been elected as the president of a farmer’s association competing with the WSGA.

Champion killed at least four attackers while holding Wolcott’s army at bay. He kept a running log of events during the siege on his cabin, even as his attackers set it on fire. Before making a break for it with a gun in each hand, Champion signed his last entry, “Goodbye boys, if I never see you again.”

Warren says Champion was killed by gunmen at a nearby ravine.

The journal documenting his final hours has most likely been doctored over the years, Warren said, but the text survives. The log’s purpose is difficult to account for, Warren said. But as a historical fiction author, Champion’s urge to narrativize the odds against him might be something Warren understands.

Warren said a biography about the famous Frontier-era lawman Wyatt Earp “hooked” him at age seven, as both an example in courage and a gateway to the study of the American settlement of the west.

“It had such an effect on me,” Warren said. “I was grateful for the way it was written, even though it was highly fictionalized.”

And his song

Rockpile Museum director Robert Henning said Warren reached out to the museum to organize the event.

While Warren’s presentations were meant to promote his two historical fiction books about Champion, the true purpose of the event, and what he said matters to him most, was to present a true account of Champion’s life and death.

“We don’t do as much fiction, but he said that this is actually about the history of it,” Henning said.

At the end of the slideshow, Warren put on a final act that’s pretty atypical for the Rockpile Museum: He sang a song, written from the perspective of Champion during his last stand, that he’d composed for the piano.

“As a wannabe historian, we’re not typically the most artistic people, (and) he’s a very creative person,” Henning said. “I think that gives him a unique ability to be a storyteller.”

It’s one thing to deliver a series of facts; it’s another to reveal how you feel about them. It was a courageous act, but in the tradition of Champion — or the best version of Champion, the one who comes out of Warren’s study — it’s possible singing his praise wasn’t a hard thing to do. Warren knows he’s right.

“Let’s put it this way. Almost everybody that’s been studied in history has been debunked,” Warren said. “I don’t think that’ll ever happen with Nate Champion … he’s the best of us.”

This story was published on September 24, 2024.