Farewell to Al — Simpson, native son and towering influence, dies at 93

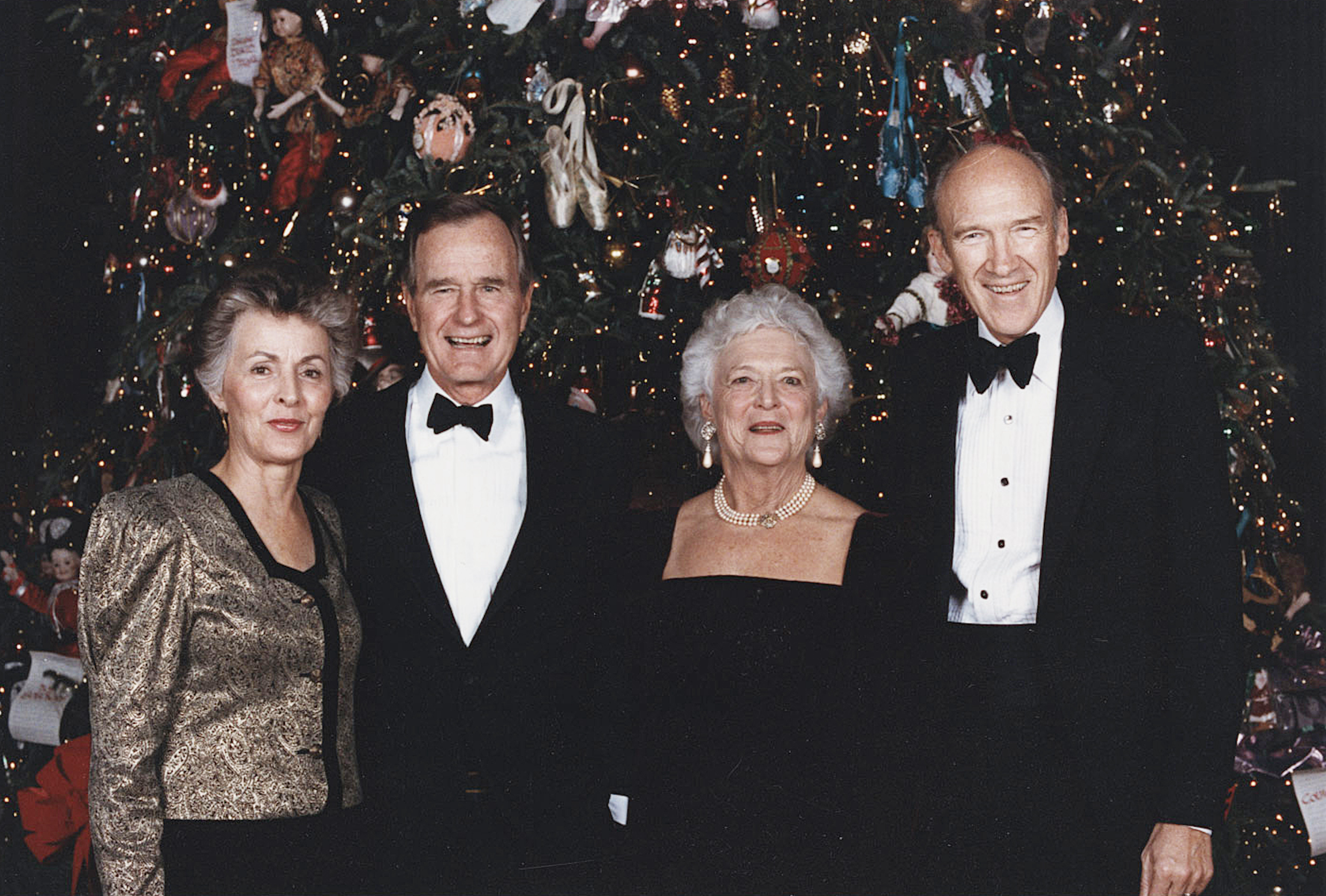

Ann Simpson, President George H.W. Bush, first lady Barbara Bush and Sen. Al Simpson attended a gala event. Courtesy photo.

CODY — Former U.S. Sen. Alan K. Simpson, who charmed Wyoming and the nation while befriending presidents in a lifetime of public service, always keeping a twinkle in his eye and a maverick nature in his heart, died March 14, 2025 in Cody of complications from serious circulation problems in his feet and legs. He was 93.

A prominent local, state and national figure for decades, the lanky 6-foot-7 Simpson, an artful story-teller who sometimes employed salty language, embodied an old-school Republican politician who got along with congress members on both sides of the aisle. He could be progressive and conservative, though at all times an entertaining speaker to audiences who appreciated his plain-spoken platform.

Simpson seemed to thrive on stories of reckless boyhood scrapes, some where his father, former Gov. Milward Simpson, had to play taskmaster, before he settled down and competed for the basketball and football teams at the University of Wyoming and then married Ann in 1954 and raised three children.

In July 2019, Simpson delivered a speech titled “Shooting from the Hip: Lessons from A Rebel.” It was a title similar to his biography, penned by longtime chief of staff Donald Hardy, titled “Shooting from the Lip.” Earlier, Simpson had written a book called “Right in the Old Gazoo.”

In that talk to the Bohemian Club on the outskirts of San Francisco, Simpson offered a glimpse of how he preferred people to view him. He noted that during his career he had avoided “succumbing completely to the absurdity and banality of political correctness.”

To him, wit was essential. “I found that a sense of humor was also vital in my political life. It sure throws off the opposition. Adversaries think, ‘Good god, what’s this nut doing trying to tell us another story?’”

The stories carried Simpson into office where his serious side emerged, if in disguise, working on matters of import for the country such as Cold War international relations and immigration policies. He supported gay rights and was pro-choice.

After serving 12 years in the Wyoming Legislature, Simpson spent 18 years in the U.S. Senate. He was also an attorney and past chairman of the board of trustees of Buffalo Bill Historical Center before it changed to Center of the West.

Simpson was also a man who might well have become vice president of the United States, except he did not want the job.

In 1988, it was apparent to many that Simpson could have been his party’s vice presidential nominee, running on a ticket with eventual President George H.W. Bush, his close friend. This was a persistent rumor and despite denying interest, Simpson had to appear on “Meet the Press” to completely debunk the suggestion.

He said he would be a liability to the ticket because “I’ve had a rather checkered career” having “punched the lights out” of many “sacred cows” in speeches on the floor of the Senate. He envisioned Democrats producing critical 30-second commercials of him that could hurt Bush’s candidacy. Being vice president, Simpson said, “is not a lifestyle I like.” He added, “I am a legislator. I love to legislate.”

Simpson turned down that opportunity and spent three terms in the Senate until 1997. In that body, he sometimes staked out populist positions. Not only did he vote against Congressional pay raises through the years, but he also returned his personal gain from them to the general treasury.

He favored eliminating honorariums given to politicians for their speaking time. There was a cap in place on that money earned, and Simpson, often in demand for his talks, donated many thousands of dollars to charities annually.

In 1990, the Denver Post wrote a lengthy feature story on Simpson. It contained a list of several of what might be termed “Al Simpson’s Greatest Hits,” blunt comments he had issued.

“I’ve often said there is a very fine line between good humor and smart ass,” Simpson said in 1989. “Sometimes I slip into smart ass.” In 1986, when attempting to convince Congress to pass immigration reform legislation, he said, “It was like giving dry birth to a porcupine.”

Simpson did not always leave them laughing. On those occasions, he took unpopular stances, including opposition to a cost-of-living increase for veterans. While the majority of the time he was media-friendly – including during his years of retirement – Simpson’s relationships with Washington reporters sometimes devolved into sniping.

The subtitle of his “Right in the Old Gazoo” book was “A lifetime of scrapping with the press.” Simpson claimed the invention of the word “gazoo” during a 1987 press conference when he was defending President Ronald Reagan during the Iran-Contra period.

In that book Simpson conceded he had “my share of satisfying experiences with the press” and had also made his share of gaffes. “Certainly, the media like to stick it to us,” he said of politicians. “And so, when it’s appropriate to do so, I’m going to stick it to them – right in the old gazoo.”

In keeping with his generally gregarious nature, regardless of how it might have crossed ideological lines and raised some eyebrows, for a time Simpson shared the radio show “Face Off” with Sen. Ted Kennedy, a Democratic from Massachusetts who was regarded as quite liberal. The show presented views from the left and right.

Simpson’s trait of openness and his witticisms resonated with citizens. In a 1989 poll, he was voted the most popular politician in Wyoming on a list that included Gov. Mike Sullivan, U.S. Rep. Dick Cheney and U.S. Sen. Malcolm Wallop.

“I’ve been kind of rambling around Wyoming for (many) years of my life,” Simpson said. “I see people from Reliance who I played basketball against in high school. I see guys I was in freshman football with at the University of Wyoming. I’ll just keep doing my town meetings, which I thoroughly enjoy, but which can be hazardous.”

Simpson could be the object of barbs from constituents who disagreed with him, sometimes in person at town meetings or other events, sometimes in those days of letters. He did not believe in letting anonymous or vituperative critics get away with breaches of civility. He may have served in public office, but in his mind that did not set himself up as a pin cushion for abuse, so he dished it right back.

On Halloweens, well into his 80s, Simpson talked down, literally, to youngsters trick-or-treating in downtown Cody, bending down in his Frankenstein costume and imitating the monster. He was called “Frankenal” and chose the part because he was a fan of the original 1931 movie and actor Boris Karloff.

Al Simpson, a legend in his time, lived a singular life of service to, and love of, Wyoming and the United States.

Al Simpson was raised in Cody. As an illustration of the family’s deep roots in Wyoming – the first Simpson in the Territory being Alan’s great-grandfather in 1862 – he recalled his aunts telling dinner-table tales of when Butch Cassidy stopped by for a Christmas meal in 1883. The famous outlaw was not yet being heavily pursued for his deviances from the law.

“They liked him,” Simpson said. Still, his grandfather Will, a prosecutor, once put Cassidy in jail

He was slow to talk as a toddler, but when he did start talking his parents joked, “We couldn’t get him to stop.”

Simpson has portrayed himself as somewhat of a juvenile delinquent whose mischief as a youth was reckless, though not the acts of a truly dangerous criminal.

Al and brother Pete, a year older, engaged in the same sports teams, and then later in life when both settled back in Cody, often made public appearances together. They had an exceptionally close bond, begun when sharing a bedroom while growing up.

As brothers might, Pete said, he and Al engaged in wrestling matches and fights. Once, their father insisted they strap on boxing gloves and take out their aggression in a more formal fashion.

“I was a little faster,” Pete said. His fists made Al’s nose bleed. Their mother, Pete said, disliked the brawling and played a permanent peacemaking role.

“That we really became brothers is owed to my mother,” Pete said. She advised them to learn to count on one another, not battle one another. “We stopped throwing stones. We took that to heart.”

Al said as they reached their teens, Pete was “a calming force. When Pete left, then I really got into trouble.”

Al characterized firing guns at mailboxes as “just stupid.” Later, while in Congress, Simpson spoke of the incident when legislators were considering a law related to juvenile crime, saying a person is not necessarily defined by what he does at 16 or 18.

When he was a 12-year-old Boy Scout, Simpson was part of a field trip to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center where Japanese Americans were interned during World War II, one that made a lifelong impression. The Scoutmaster said they were going to have a jamboree with similar-aged boys behind the fencing just as if they were a local troop. On that occasion, Simpson connected with a displaced California boy named Norman Mineta. As adults, Mineta, who became U.S. Secretary of Transportation, and Simpson, who was serving in Congress, renewed their friendship.

Years later, in July 2019, Simpson, using a cane, Mineta, using a walker, visited again at Heart Mountain during its annual Pilgrimage.

At different times, Simpson said the lessons from the internment of Japanese Americans had to be absorbed. “It could happen again,” he said, noting how American society had demonstrated so much anti-Muslim emotion after 9/11.

In consecutive years, 1948 and 1949, the Simpsons sent first Pete, and then Al, to Cranbrook Schools in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., as a sort of finishing school. They both discovered beer, while Al also discovered the Detroit Tigers which turned him into a big Major League Baseball fan.

Before his Michigan sojourn, Al graduated from Cody High School with the class of 1949. By that time he was aware of a young lady from Greybull named Ann Schroll. Simpson said he spotted her at a basketball game and told a friend, “Look at that gal.” Ann said much later she and her twin sister, Nan, had been on the lookout for tall boys. Simpson was at his football weight at the time, roughly 250 pounds. Another strike against Al at the time in Ann’s estimation was an inability to dance.

It wasn’t until later in Laramie that he encountered her again. Ann was dating someone else at the time and Al recalled the other guy as “handsome and (he) had a big car.” Slick transportation aside, Al made a better impression this time around.

“We were just a bunch of hicks over there in college and we started to go together,” he said.

They stayed together through Ann teaching school for a year in Cheyenne and Al completing college. The Simpsons married June 21, 1954, as Al was beginning a military commitment that took the young couple to Fort Benning, Ga. and then Germany, until 1956. Lt. Simpson disliked his Army time and despised being bossed around.

Simpson earned his law degree from the University of Wyoming, and the Simpsons had their first child, Bill, in 1957. Colin and Susan followed.

Typically, Simpson employed humor to describe the success of their long love affair. “Behind every successful man is a woman rolling her eyes,” he said. “I can hear her clearing her throat like a dog whistle.”

That meant Ann was telling Al to cease speaking. He looked for a graceful way to shut up by using the phrase, “in conclusion.”

Public life

Simpson spent more than 12 years in the Wyoming Legislature before pursuing a bigger challenge. He sought a U.S. Senate seat from the Cowboy State in 1978 and, after winning the election, was sworn into office Jan. 23, 1979.

Over his years in the Senate, Simpson greeted Judge Antonin Scalia to his Senate confirmation hearing to the Supreme Court with the phrase, “Welcome to the pit,” favored President Reagan’s economic sanctions on South Africa, criticized longtime Senate staff personnel, spearheaded nuclear waste disposal planning, and urged a 10% budget cut on all environmental programs.

And although he did not choose to run for vice president, Simpson was chosen by his Republican colleagues as majority whip. A vote for Simpson in this position was an endorsement of a collegial working relationship with both sides of the aisle.

The den-office of Simpson’s Cody home is a man cave of sorts. Papers are stacked high, bookshelves filled, autographed baseballs displayed, and walls highlighted with photographs of Simpson with famous figures.

He once refereed a tennis match between President George H.W. Bush and baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams. Simpson owned a copy of the book “My Turn At Bat,” written by Williams and John Underwood. Williams inscribed it, “To Al, a great American and a super guy, Best Always, Ted Williams, 1988.”

Almost immediately after his arrival in D.C., Simpson drew attention for his unorthodox methods, often defined by his jokes. A Washington Post feature soon appeared with this description: “A senator who finds renewal in (humorist James) Thurber and (cynical newspaperman H.L.) Mencken, keeps western originals by (Charles) Russell and (Frederic) Remington on his walls and sees the Senate as something of a funny farm, deserves a closer look.”

Simpson, it was said, was “one of those refreshing breezes” in the halls of Congress. Simpson said he was just being himself.

“If you don’t know who you are before, you’ll never find out here,” he said in 1980. “I’m trying to be the same person I’ve always been and see how it works in the U.S. Senate.”

In that 2019 speech to the Bohemian Club, Simpson repeated his famous wisdom, “If you have integrity, nothing else matters and if you don’t have integrity, nothing else matters.”

That is a precept Simpson tried to follow during his career in politics.

‘Senior geezer’

After his time in the Senate. Simpson taught classes at the University of Wyoming, including a political science course at the time the nationwide buzz had him signing on for a cabinet position after the 2000 election of George W. Bush as president and Simpson’s friend, former Wyoming Congressman Dick Cheney, as vice president.

“The answer is not ‘No,’ but ‘Hell, no,’” Simpson told his class. “I will only be senior geezer counselor.” He also taught at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard and again practiced law in Cody.

In 2001, at 70, Simpson had a cancer scare. He was treated for prostate cancer in Houston, and rebounded. A year later he appeared with the Boston Pops Orchestra under conductor John Williams, reading passages from William Faulkner’s novel “The Reivers.”

In 2010, Simpson was appointed by President Barack Obama to the bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform and endorsed campaign finance reform.

Simpson joined the board of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in 1968, and served as chairman 1997-2011. Recently he became chairman emeritus of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Al Simpson, a legend in his time, lived a singular life of service to, and love of, Wyoming and the United States.

This story was published on March 14, 2025.