Medicine Lodge pottery shows Mountain Crow may have lived near Big Horns in 1300s

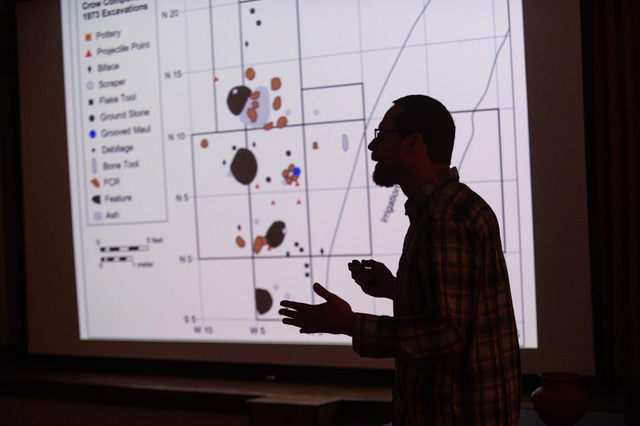

State archaeologist Michael Page shares information on recent digs and artifacts found at the Medicine Lodge Archaeological Site during a presentation Wednesday at the Campbell County Public Library in Gillette. Photo by Ed Glazar, Gillette News Record.

GILLETTE — Fond memories come to the surface when Terry and Janet Tharp think back to moments they experienced as children at what’s now called the Medicine Lodge Archaeological Site.

Growing up in the late 1950s and 1960s near Hyattville, the now married couple said the site wasn’t called that yet. It was simply a ranch — an area where Janet was taken for picnics on a school field trip and the home of children Terry went to school with.

“The kids that lived there on that ranch, they would go out and they would find arrowheads, hide scrapers and all of that,” Terry said.

“But you didn’t really hear much about (the excavations) until later,” Janet added.

The area then was known for its carved rock-art images or petroglyphs that spanned hundreds of feet of sandstone. The art created thousands of years ago by Native Americans living in the area piqued curiosity in many.

But it wasn’t until later that anyone discovered there was more hiding beneath the layers of dirt on the ranch than anyone could see carved into the face of the sandstone found about three hours west of Gillette.

“You could go out and you could see those cliff drawings up there,” Terry said. “At the time, we thought it was pretty interesting but we didn’t know what was out there, no idea.”

Years later, he began to hear about excavations completed at the site — digs finding thousands of artifacts that have since recreated a general timeline for when the Mountain Crow people first came to Wyoming. On Wednesday, Michael Page, who works in the Wyoming State Archaeologist office, shed light on the most recent digs that took place in 2021 in a presentation at the Campbell County Public Library.

Those results suggest that the Mountain Crow people first arrived in Wyoming hundreds of years earlier than scholars initially believed, potentially traveling to the west slope of the Big Horn Mountains beginning in the 1300s rather than the 1600s.

Behind the dig

Page said two main groups of Crow Native Americans lived in and along the Yellowstone River — one group was known as the River Crow who mostly lived in Montana, while the Mountain Crow lived most of the year in Wyoming.

He said there are many tales about how the Crow first came to Wyoming but no one really knows when they first arrived, adding that the “Handbook of North America Indians” places members of the tribe traveling to the Big Horn Mountains area in the 1600s.

Other stories exist of a group of Awatixa who lived on the Missouri River traveling west after an argument and vision by their leader, Page said.

Medicine Lodge Creek seems to be an area where everyone would settle down for a few winter months, based on excavations completed in the last 50 years. The creek’s most important information lies in the pottery found at the excavation site.

The most recent dig in 2021 lasted for 16 days in the center of the state park where kids and adults could all join in the excavation. All together, Page said about 200-300 people came through the area and about 20-30 people helped with the digging.

Information from a few previous excavations also provided Page with where to focus the resources and how the group should dig.

Pottery findings

Excavators dug three blocks down about 2 feet where they found distinctive pottery and a number of fire pits.

“We found a bunch of these fire pits,” Page said. “Most of them were shallow little basins filled with ash and charcoal that provided so much botanical remains … we also found a lot of bone.”

Thousands of artifacts were found in the well-preserved layers of soil, with the older artifacts found deeper within the ground’s layers. The success of the dig stemmed in part from how well those items were preserved, something uncommon in some archaeological excavations.

“I’ve worked at sites all over this country and I’ve never seen a site as well preserved and nice to dig than Medicine Lodge,” Page said.

Pottery found at the site showed a distinctive checked-pattern, or check-stamping, made by carving a design into clay that’s then shaped into a pot using a wooden paddle.

“This pot was actually made out of a solid lump of clay that was pounded into shape with a paddle,” Page said, raising a replica Crow pot to show the audience. “It leaves that nice characteristic mark on the outside of it and the only other place you find that is on the Missouri River in the villages of the Hidatsa and Awatixa, the relatives of the Crow.”

The pottery also had a sharp corner on the pot’s shoulder not found in other tribe’s pottery.

In comparison, the Fremont people created pottery by stacking coils and smoothing them over, Page said. The pots were smooth and polished versus the Crow’s tempered exterior, typically rough from the crushed bits of sand and rock used to make the clay easier to work with or seal in cracks.

Ute pottery usually has a knob on the bottom and fingernail markings visible on the outside of the pot.

Because each tribe’s pottery is so unique, Page said the evidence points to the Mountain Crow living on the west slope of the Big Horns beginning in the 1300s, not the 1600s.

“The idea is that the group of probably Awatixa split off and they came West,” Page said of the updated timeline. “And they brought with them the pots they knew how to make and the women who knew how to make them and they just stayed. And these people eventually became what we call the Mountain Crow.”

Page said he didn’t think anyone found this out until recently because there are so few sites in Wyoming that include pottery artifacts. The lack of pottery could be because the pots were too much for the hunters and gatherers to carry with them, as they were constantly on the move.

He believes Medicine Lodge was a winter camp because of the number of fire pits found in the dig but also the protection the canyon offers. While the Crow would need to move around more frequently in good weather to find more game to hunt, they would normally hole up during the winter for a few months at a time after a buffalo hunt.

Terry Tharp said he could see why the canyon offered a great spot to shelter during the colder months.

“The whole area, the whole canyon,” he said. “I could see why it was a wintering spot because that whole canyon is very sheltered. Like (Page) said, there’s no wind and if it snows it falls straight down. It can be 20-25 degrees warmer in that canyon than any of the surrounding areas.”

Although the exact time periods and details surrounding the Crow’s arrival in Wyoming may never be known for certain, the Medicine Lodge site allows for conversation surrounding the history and stories of the peoples who knew the land thousands of years ago to continue.

For the Tharps, it also gave more insight into the land they first saw as children — filled with so much more history than they imagined.

This story was published on April 6, 2024.