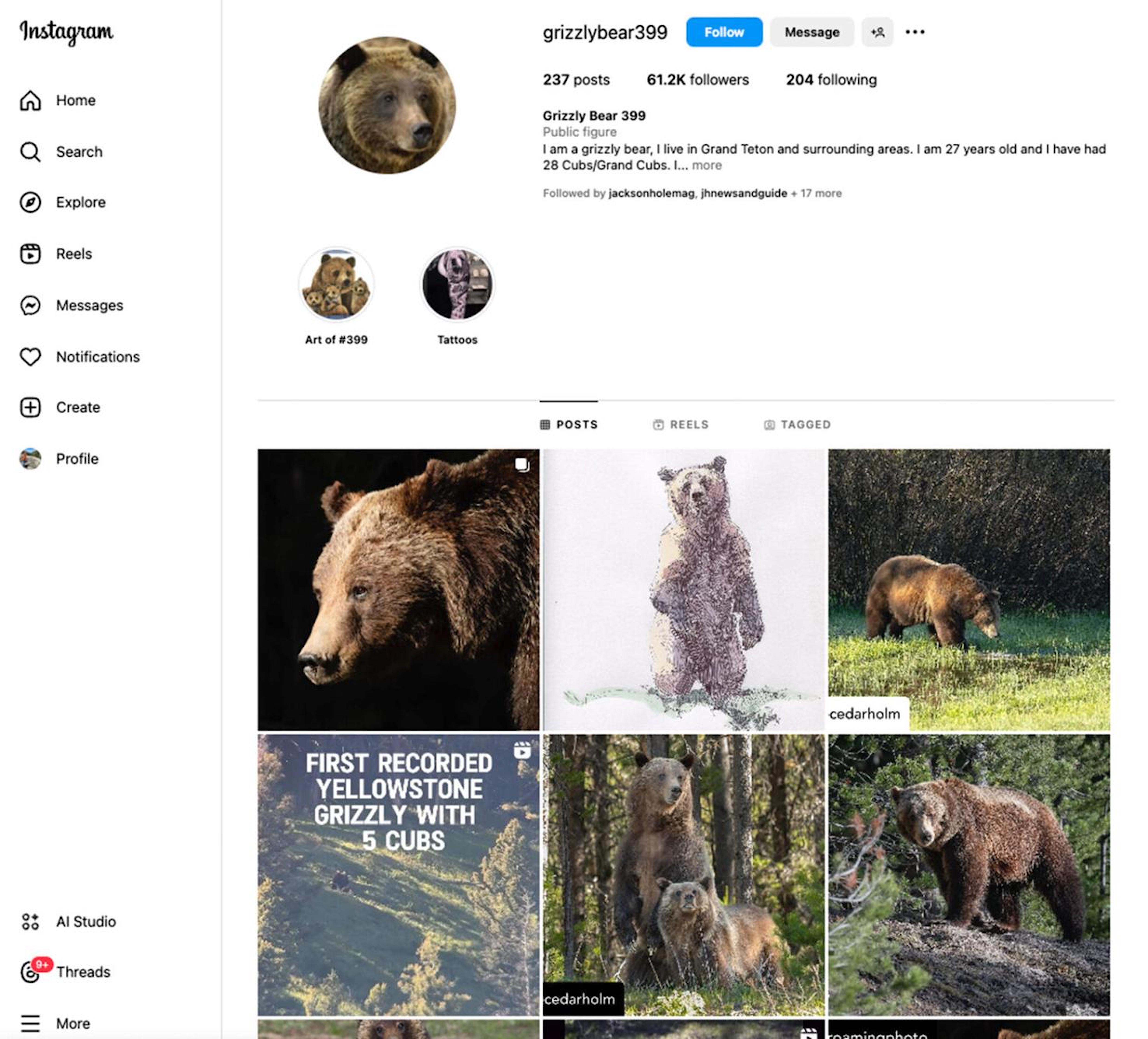

Grizzly 399 as influencer

Grizzly 399’s Instagram was prolific in the digital ecosystem and reached thousands of people with its posts and photographs. Screenshot from Instagram.

Social media drove meteoric rise that anonymous creators tried to manage.

JACKSON — When Tenley Thompson decided to try being the voice of a famous grizzly bear online, she didn’t start with Grizzly 399, the most famous bear in the world. Instead, she started with her daughter, Grizzly 610.

Unlike 399, who was relatively tolerant of human presence, 610 is known for having an attitude — a comportment that Thompson thought would play well on Twitter, which was ballooning at the time.

“She’s charged plenty of people,” Thompson said of 610. “My favorite is when they tried to push her off the Moose-Wilson Road with rubber bullets and she charged the patrol car and jumped on the hood.”

For about five years, Thompson tweeted about eating elk, asked for portraits from News&Guide photographers and reposted articles about delisting. But in the mid-2010s, Thompson went bigger.

On Instagram, she acquired the handle @grizzlybear399, hoping to prevent someone else from commercializing the famous bear’s likeness. When Thompson, a wildlife tour guide, started seeing people posting misinformation about the famous bear, she activated the account to set the record straight.

By the time 399 died in October, the account had more than 61,000 followers — about 8,000 less than 399’s main documentarian, photographer Tom Mangelsen. The photos and videos Thompson have posted have garnered thousands of views.

But for the past decade, Thompson remained anonymous. This article is the first time she and other handlers of Grand Teton National Park’s famous bears’ online profiles have identified themselves publicly.

“It was never about me, and it was never about my ego, and it was never about what I wanted,” Thompson said in early December. “It was about trying to do good things for the bears I loved.”

For Thompson and other humans who doubled as famous grizzlies online, that meant choosing not to commercialize the account and, as the bears’ stocks rose, trying to post information that encouraged people to behave better around them, whether by staying more than 100 yards away from them in Teton Park or acquiring bear-resistant trash cans for their homes in Jackson Hole.

Acutely aware of 399’s popularity and the ills that came with it — and her own role as the general manager of a wildlife tourism company, Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures — Thompson said she never tried to make 399 more popular.

Instead, she tried to dispel misinformation, like claims that 399 had never hurt a human. She countered the idea that 399, who was tolerant of people, actually liked people. And she tried to disrupt mythologizing.

“What’s fascinating about her is the struggles she goes through and the losses and the recovery and her willingness to carry on and her endurance and her resilience through terrible circumstances,” Thompson said. “When we turn it into this just simplistic ‘Look at this adorable mother in her cute cubs, and she’s a cute teddy bear,’ I think we do her a disservice, and that’s what I wanted people to see.

“I wanted people to see the real bear,” she said.

Social media made Grizzly 399 the bear of the digital age. But it also attracted thousands of people to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Their eagerness to see 399 and the other famous bears in Teton Park often got the best of them — and oftentimes the bears. Even well-behaved visitors challenged bear managers in the park to find new ways of keeping people and bears safe as the number of people at roadside bear jams exploded. Other visitors behaved badly, feeding the offspring of famous bears like Grizzly 610. After leaving their mother, two of 610’s emancipated cubs were trapped and killed for displaying boldness around people.

“We love them probably to the point where we think that we’re all doing damage to them. We’re habituating them,” said Candy Brad, a retired veterinarian and wildlife photographer. “I use ‘us’ as all the photographers, all the tourists, all the people that chase them and show up and get in their face.”

399’s online following first started building in 2006, when she began raising cubs near the road in Teton Park. After humans wiped out grizzly populations, only 136 bears remained in Wyoming by 1974, the year before they received Endangered Species Act protections. All those bears were in Yellowstone National Park. After decades of intensive recovery efforts, 399 was the first female with cubs to publicly take up residence in the Tetons. She became a symbol of grizzlies’ recovery — two years after Facebook was founded.

In 2006, when 399 was first spotted near Oxbow Bend, bear watchers’ adrenaline surged onto the internet.

Sue Cedarholm, one of the first photographers to follow the famous bear, remembered people taking pictures in the morning and uploading them to Facebook that afternoon, which created competition among rank-and-file photographers.

Five years later, when 399’s daughter 610 adopted one of her mother’s cubs, Facebook was in full swing and Instagram had just been founded. The adoption story went wild. While managers knew grizzlies would embrace one another’s cubs, the public had never seen it happen before. 399’s popularity ballooned.

“Social media is what really got her going worldwide,” Cedarholm said. “And then, when she had the quads” — the four cubs 399 emerged with during the COVID-19 pandemic — “that put her off the charts.”

But Thompson, 399’s voice on Instagram, cautioned that it wasn’t just social media that helped 399’s popularity explode. In her view, the rise of more affordable, high-quality camera equipment and the fact that 399 was the first sow to take up visible residence in the Tetons were other key contributors.

“I think social media had an irreplaceable impact on her popularity,” Thompson said. “But I think it was a combination of all of those factors to create sort of this perfect storm.”

Cedarholm admits that people like her and Mangelsen, who has authored multiple books about 399, helped propel 399’s meteoric rise online. But she argued that they, like Thompson, also tried to counter 399’s often problematic ascent with messaging.

“Yes, we helped create the problem,” Cedarholm said. “But then we’re also trying to put out information to counter it, to help conservation, things people can do and how to act when you’re around bears.”

In the digital grizzly ecosystem, folks like Cedarholm and Mangelsen were among the first wave of influential figures, traditional wildlife photographers who migrated to social media over time.

Later came people who chose to adopt campy ursine personas online like Thompson and Mike Cavaroc, a Kelly-based photographer who ran 399’s Twitter account.

More recently, people like Bo Welden have emerged on the scene. They work as influencers, creators who share personal stories to talk about grizzlies and wildlife in the Tetons.

Cavaroc, 399’s Twitter handler, admitted that playing a bear online was fun. He, like Thompson, chose to stay anonymous because he didn’t want to get crossed up promoting his own photography. But he also wanted to let people’s imaginations run wild.

“I think it was just more fun for people to imagine that 399 was actually using Twitter, even if everybody knows it’s not real,” he said.

Cavaroc regrets not continuing with 399’s Twitter. He stopped in 2017 to give himself a break from social media.

“I really enjoyed providing that voice,” he said. “Wildlife can’t speak for themselves, but that really gave me the opportunity to speak up for public land protection, wildlife rights and have a platform.”

But now, as social media transforms into a new influencer-driven culture that promotes places and experiences, creators worry about its continued impacts on grizzlies and the ecosystem going forward.

“It’s just, how many people can see that and have access to it with maps and routes and blogs and forums that just tell people, ‘OK, go exactly right here and do these things,’” Welden said. “That’s freaky.”

Thompson, for her part, has always felt conflicted about being the voice of a famous bear on Instagram. She has always heard criticism that the Instagram account made 399 famous, which she disputes.

“She was popular long before I came on the scene,” Thompson said. “I didn’t create her popularity. I certainly gave it more of a national audience than it would have had otherwise.

“But I’d like to think I did far more good that way,” she said.

This story was published on December 11, 2024.